Elliott M. Antman, M.D., Jane A. Leopold, M.D., William H. Sauer, M.D., and Paul C. Zei, M.D., Ph.D.

In this instructional video, Drs. Jane Leopold, Elliott Antman, William Sauer, and Paul Zei provide an overview of the classification and diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, management strategies, and mitigation of stroke risk with anticoagulation therapy.

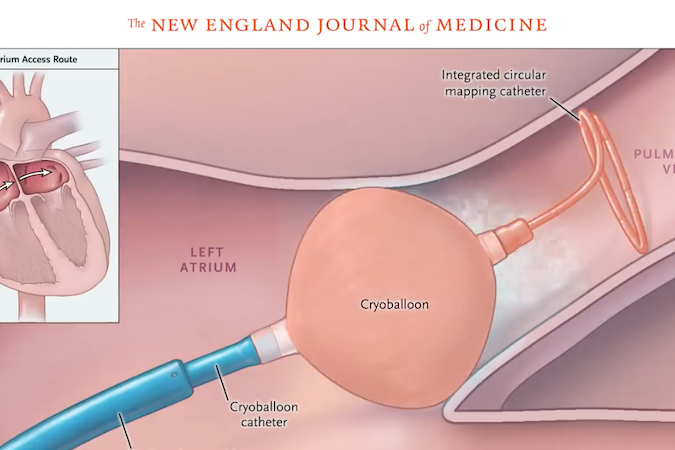

The video also focuses on the new rhythm-control strategy of catheter ablation therapy, with attention to the success rate, potential complications, postprocedural monitoring for recurrence of atrial fibrillation, and consideration of ongoing anticoagulation therapy in these patients.

Published on nejm.org